Writing Portfolio

Want a free sample?

Here’s a taste of my writing. It’s just a spoonful, but you’ll get the idea.

Copywriting & UX Writing

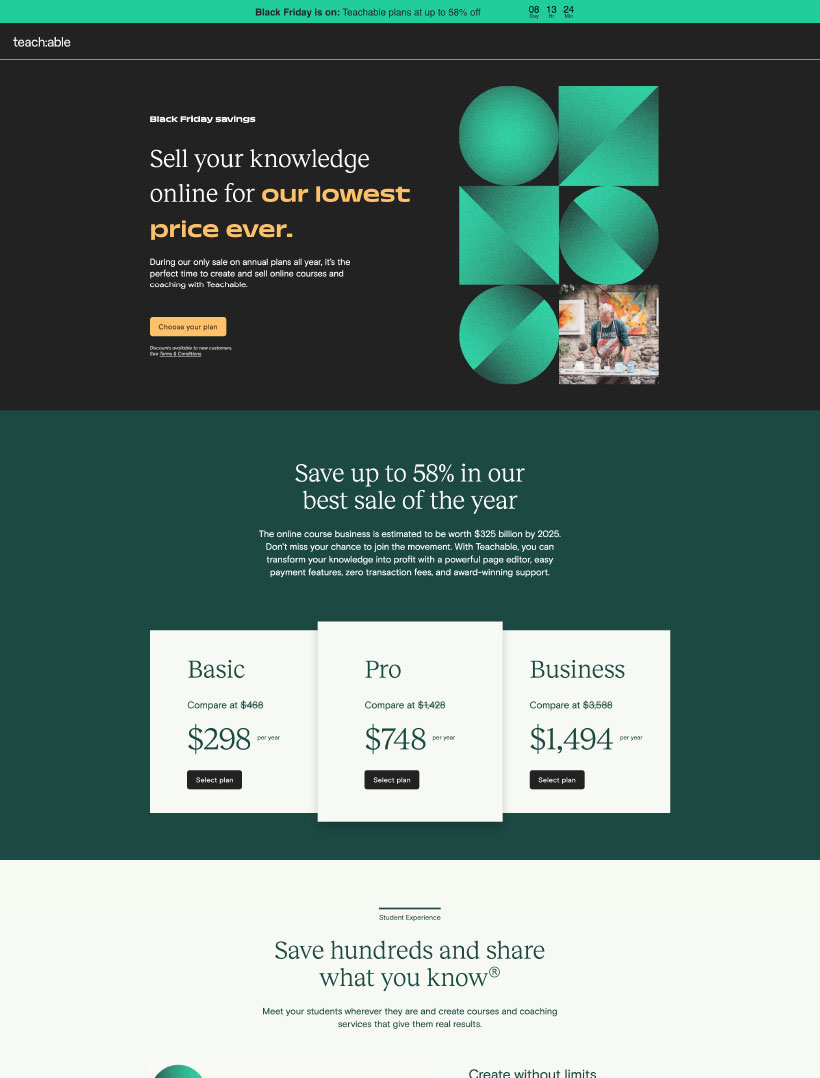

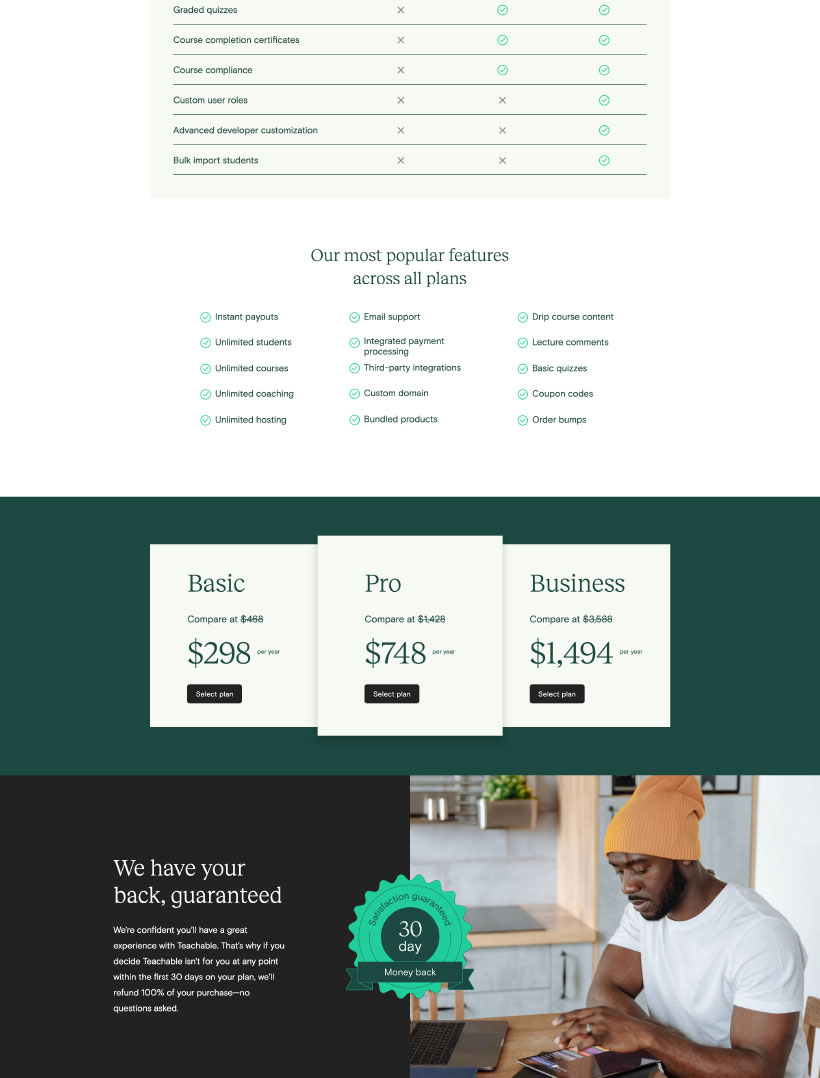

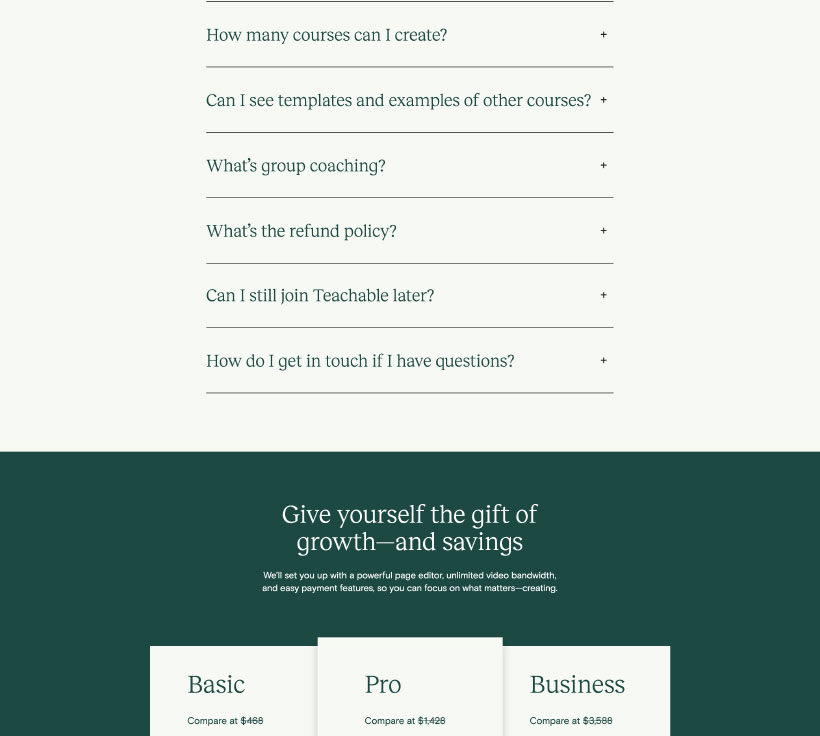

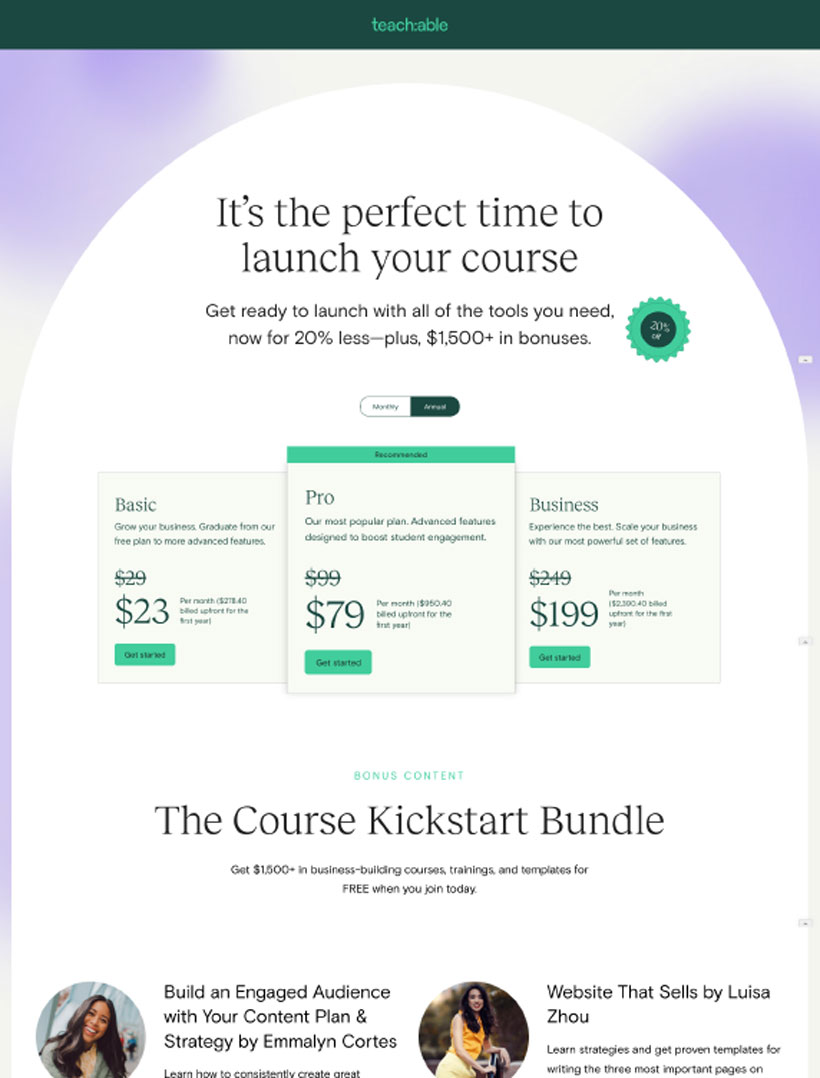

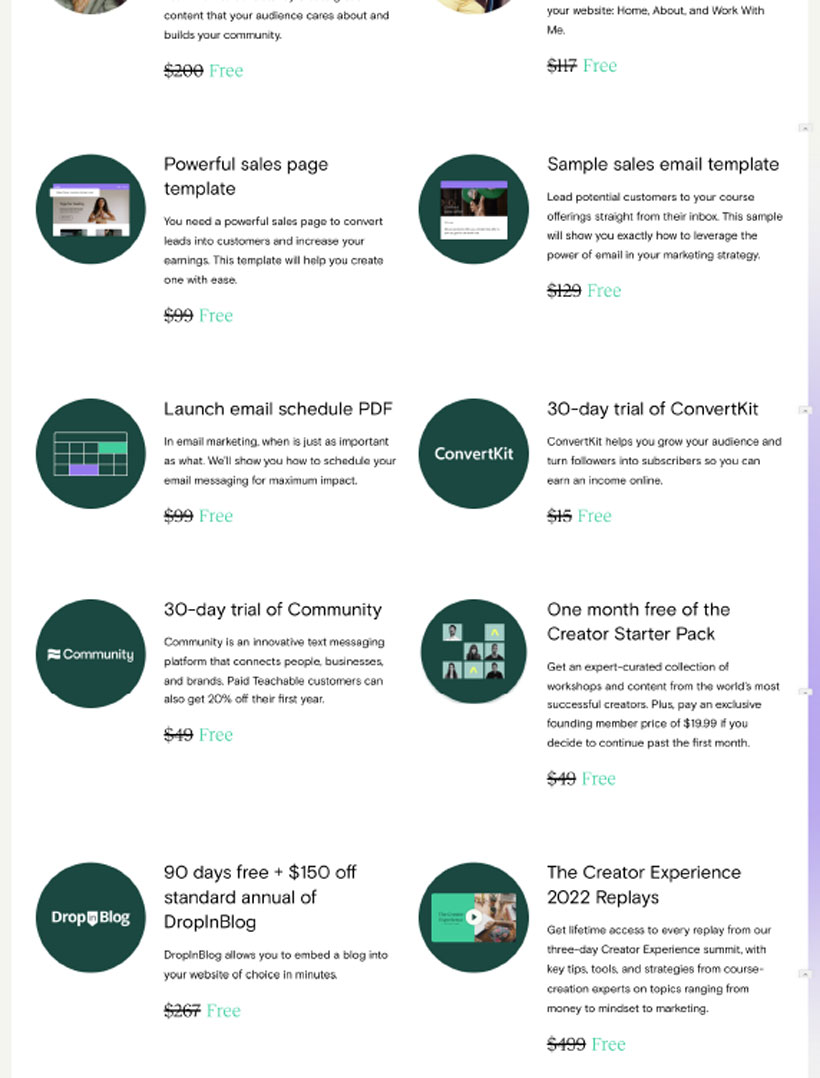

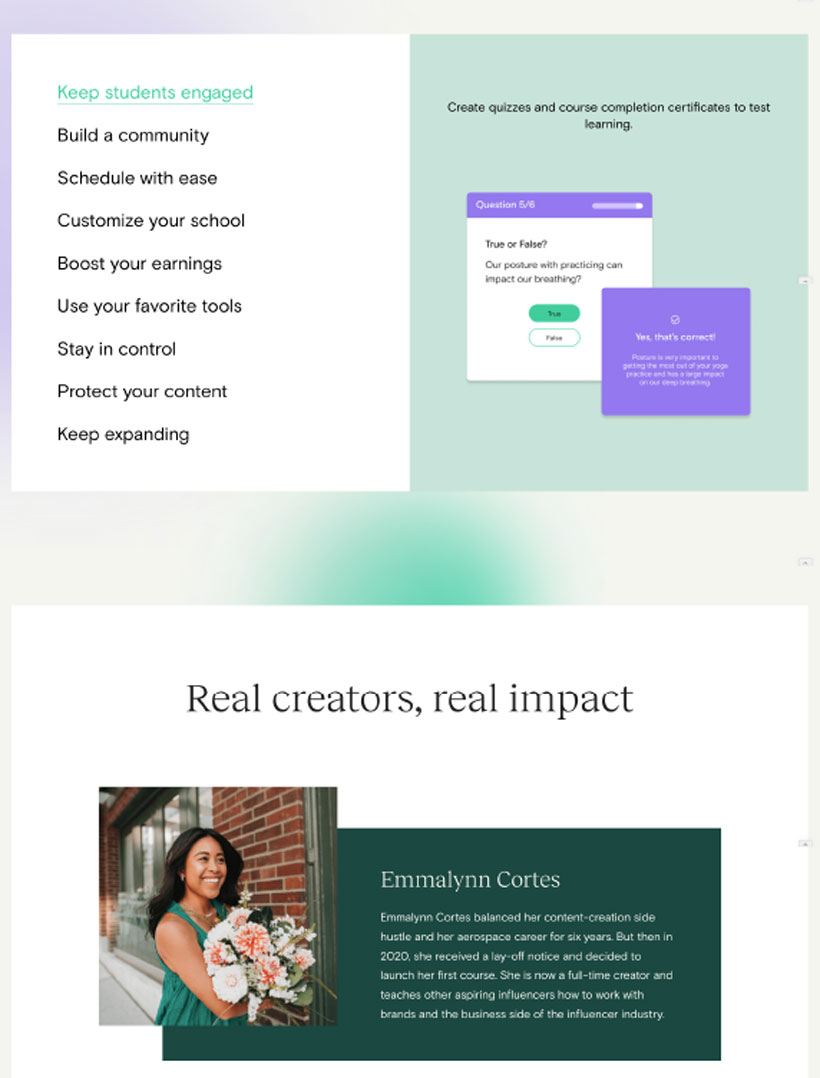

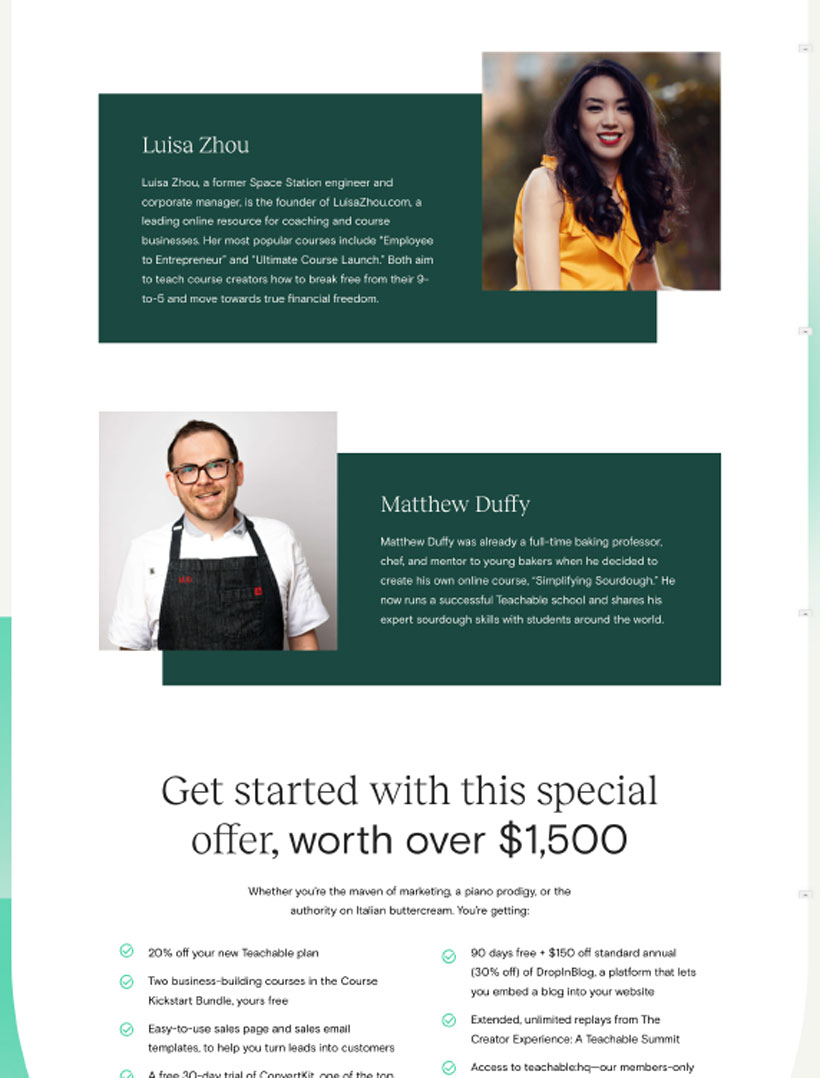

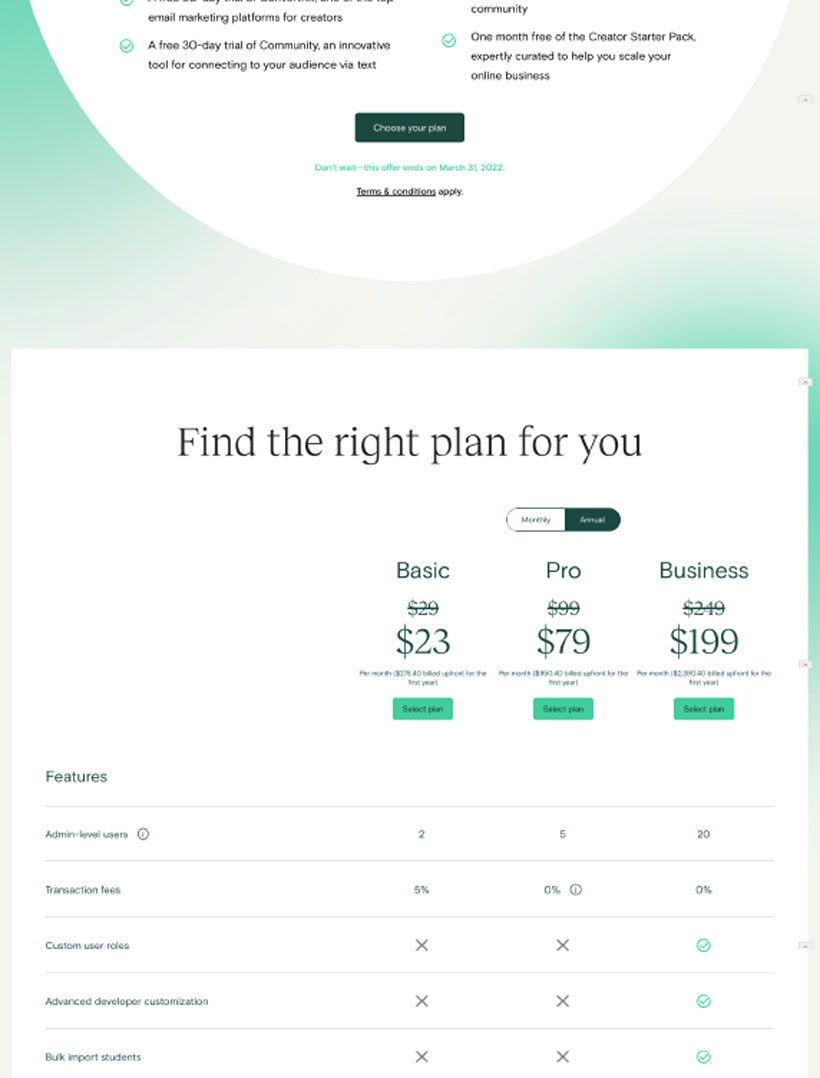

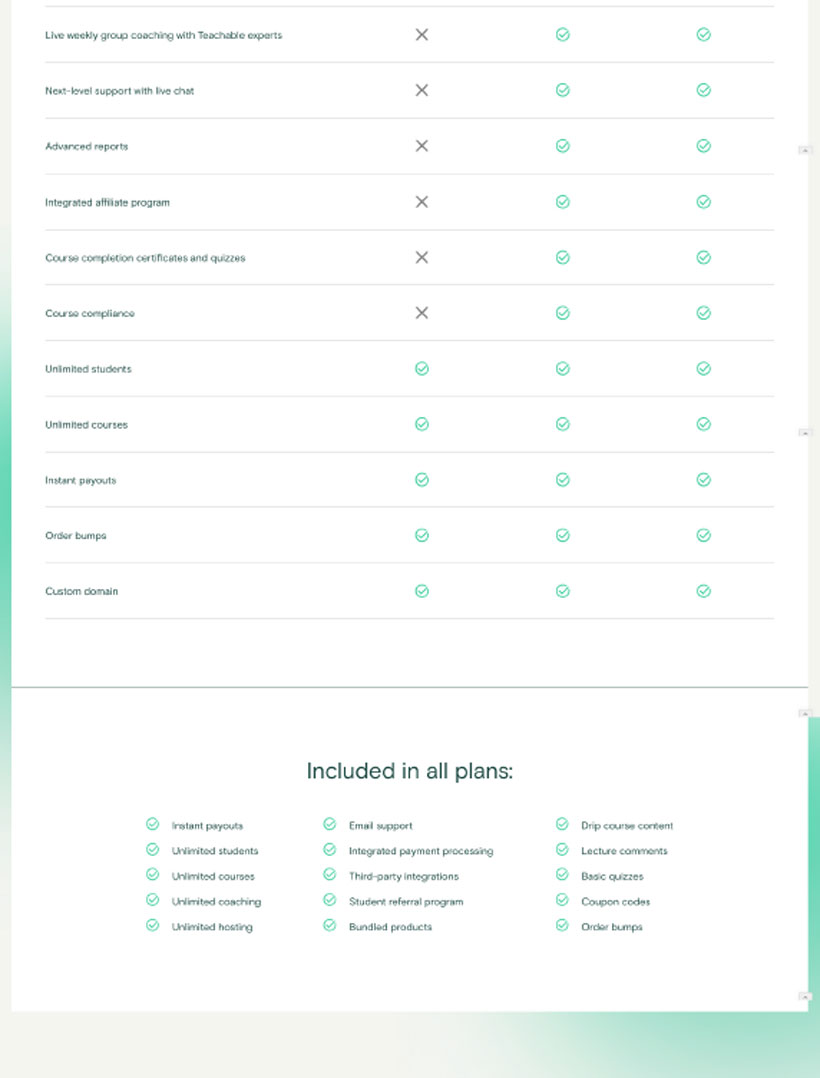

Teachable

Project: Black Friday Campaign 2021 | Scope: Copywriting for landing pages; sales, abandoned cart, and downsell emails; affiliate swipe copy; homepage popups and banners

Project: Creator Summit 2021 | Scope: Copywriting for landing pages; sales, abandoned cart, and downsell emails; homepage popups and banners

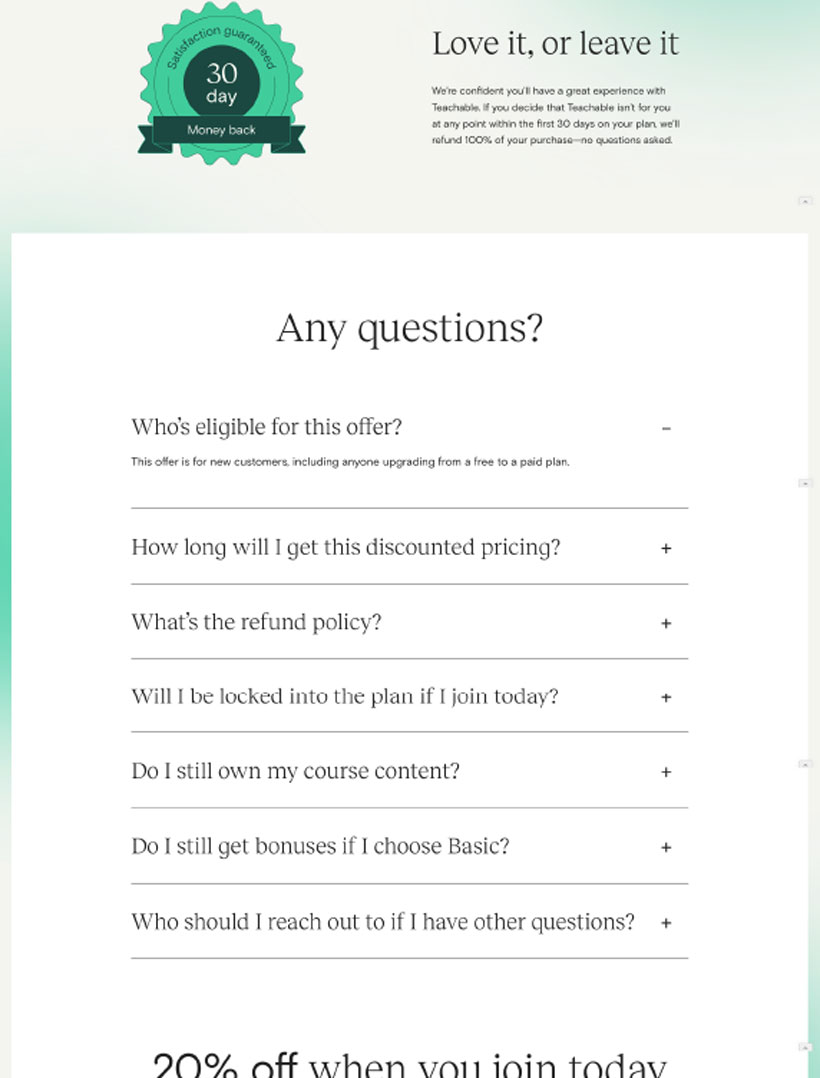

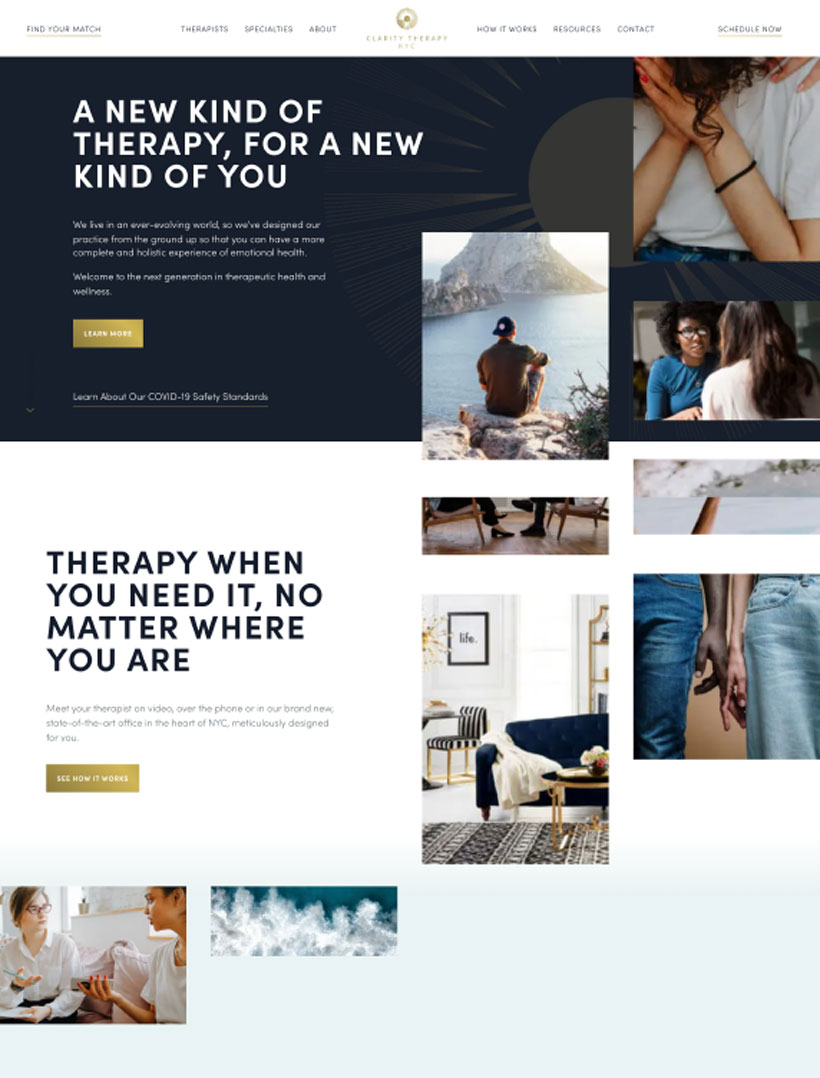

Clarity Therapy NYC

Project: Full website rewrite and redesign | Scope: Copywriting for entire site and rebrand collaboration

Sari Broda

Project: Full website rewrite and redesign | Scope: Copywriting for entire site

Journalism Clips

The Content Strategist

To repost or not to repost? That’s no longer the question.

Why? Because the answer is obvious: Repost. Always. Or almost always, at least.

Today, we’re talking about the advantages of reposting an article that runs on your blog or digital publication in its entirety on another platform—like Medium, LinkedIn, or even email.

If your goal is to get as many people to read your content as possible, it just makes sense—whether your goal is to build your brand, attract new customers, or a combination of both.

Let’s look at some of the most fruitful places to repost your content.

read more

Columbia Journalism Review

When the remains of Kim Wall’s body washed ashore in Denmark this summer, the anxieties and fears of female journalists were put into stark, heartbreaking tangibility. Wall had traveled the world as a freelance reporter, ventured into dystopian political terrain and crumbling cities, but it was in Copenhagen, a city not far from the Swedish town where she grew up, and on a reporting trip that should only have cost her a few hours, that she lost her life.

On the night of August 10, Wall set out on the UC3 Nautilus, a homemade submarine built by Danish inventor Peter Madsen. The last pictures taken of Wall show her atop the vessel with Madsen, smiling for the camera as the pair prepared to depart for an evening voyage around Koge Bay. She was reported missing the next day, and on August 21, a dismembered torso was found on a nearby beach that was later confirmed through DNA analysis to be hers.

The story has been widely reported for its unique horror, but also because it taps into a fundamental reality for female journalists, who often must put themselves in environments women are told to avoid. For women, reporting risks come not only in the form of stray artillery fire and government persecution, but in being alone with men.

read more

Ashley Gilbertson has made a small ceremony of stopping for a cup of coffee and a cigarette on his way to an assignment. One February morning in 2010, the scene of that ceremony was Earleville, MD, a farming town so tiny, and with so little demand for caffeine, it doesn’t have a coffee shop. Not even the gas station serves a steaming cup. So Gilbertson sat on a curb in front of the station and washed down his smoke with an energy drink, while some teenagers chased chickens around a pump.

It was a simple moment, but one that stayed with Gilbertson as he finished his cigarette and drove to the home of Brandon Craig. Gilbertson was on his way to photograph the Army corporal’s bedroom. Craig died in Husayniyah, Iraq, on July 19, 2007, blown up by a roadside bomb. He was 25. His room was small and clean. A stuffed raccoon rested against the pillows. A quilt in the shape of the American flag clung to one wall, the lyrics to “America the Beautiful” running along its white stripes.

read more

Outside the doors of the Waldorf-Astoria on Tuesday night, protesters pause and wait for the next video camera light to turn on. Buttressing both sides of the Park Avenue entrance, they stand in the drizzle clutching umbrellas, dozens of miniature Ecuadorean flags, and signs bearing journalist Janet Hinostroza’s face, emblazoned with the words, “VERGUENZA DEL PERIODISMO” (shame of journalism), “VENDE PATRIA” (sells homeland), and, on another, exhibiting perhaps the most ironic of the night’s statements, “CPJ: ENEMIGO DE LA DEMOCRACIA Y LA LIBERTAD DE EXPRESION” (CPJ: enemy of democracy and freedom of expression). As the next camera starts to roll, they chant.

Inside, Hinostroza—dressed in a long, shimmering ballgown—mingles with other members of the media as she awaits the night’s ceremony, in which she will be honored along with three other journalists with an International Press Freedom Award by the Committee to Protect Journalists. The protesters don’t seem to phase her; but then, she’s used to it.

read more

With the exception of Friday Sabbath, Kolkata’s Magen David Synagogue is almost always closed. When the doors do open, occasionally someone enters, lights a candle, and prays. But mostly, the Magen David sits quietly. Upstairs, the balcony is lined with rows of dusty wooden chairs and pews, leftovers from the synagogue’s last service in 2013. (The most recent, prior service took place in 1988.)

Soft, sandled footsteps do sometimes echo through the main hall, but they belong to the caretakers—who are Muslim and Hindu, not Jewish. These days, it’s hard to find a Jew in Kolkata. The bustling capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) is home to some 14 million people. Most are Hindu, some are Muslim, and a few are Christian, Jain, and Buddhist. So small is Kolkata’s Jewish population that it doesn’t even appear in the city’s census. Yet tucked into corners of the city are the Magen David and other synagogues and Jewish schools, remnants of another era.

read more

The Weekly Alibi

James Aranda and Jaime Chavez are looking out over the West Mesa, on land that runs through their blood like the Rio Grande runs through Albuquerque. They are standing on Atrisco land, pointing out the boundaries of their heritage—the east bank of the Rio Puerco, the west bank of the Rio Grande, Pajarito Road on the south and St. Joseph Drive by St. Pius High School on the north. I smile when I realize what 82,000 acres means.

The Atrisco Land Grant, which hugs the cusp of our city, was founded in 1692, when Don Fernando Duran y Chaves II settled there and was granted the land by the King of Spain. Since that pivotal moment in time, the story of Atrisco (or Atlixco, which means “place by the water”) has been long, complex and bittersweet, gnarled and twisted by war, treaty and revolution. It survived the Pueblo Revolt and was secured by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, remaining one of the oldest existing land grants in the United States.

Now, it may be up for sale.

read more

Robert Brumley wants to build a ghost city in the middle of the desert. The CEO of Pegasus Global Holdings, a technology development company, has a surreal plan: Construct an entire city spanning 20 square miles over two years. Build enough homes to shelter 350,000 people. Erect a downtown, cobble together a warehouse district, save some green space, put in an “old town,” even run an interstate right through the middle of it. But don’t let anyone live there.

Humans are disruptive variables.

read more

Eggs, milk, peanuts. It didn’t look good.

I had spent the last hour scavenging the isles of La Montañita Co-op, and that’s what I was left with: eggs, milk, peanuts. I was hungry just looking at them. I offered my meager basket to the cashier, pausing to turn around and grab a hauntingly aromatic chocolate chip cookie from the deli counter behind me. If all I had to eat for the next seven days were eggs, whole milk and peanuts, I was going to enjoy my last meal, and I was going to have dessert.

I watched the clock on my cell phone strike midnight, rubbing my fingers together to erase the chocolate from their tips. This was it. For the next week, I would eat only food grown in New Mexico. In the middle of February, I knew it would be difficult. But when I opened my fridge door and saw two cartons and a bag of nuts staring back at me, I wondered if it was even possible. Preparing myself for starvation, I trundled off to bed. Tomorrow I was going “shopping.”

read more

Turn on a faucet. Any faucet. If the faucet you’ve chosen is in Albuquerque, the water that surges out of your hose, into your kitchen sink, onto your head or down your toilet is older than Christianity. Older than the Roman Empire. At least as old as the end of the last Ice Age. This 10,000-year-old water is pumped from beneath your feet and forced to the earth’s surface from a fractured network of vessels that make up the city’s aquifer.

Come December, what pours out of that faucet will come from a river instead.

Albuquerque’s aquifer is shrinking. The size of our population, coupled with bad conservation practices, lowered the water table not only under our city, but throughout the entire Middle Rio Grande Valley. Left alone, water quality could become an issue within 25 years. Within 35 years, pockets of land over the aquifer could begin to sink. Realizing this potentially catastrophic effect, back in 1997 the City of Albuquerque came up with a plan.

read more

“No!”

We were searching for our KI, which, if LuAnn our instructor was correct, was nestled in the midpoint of the lower balls of our feet. We stood, knees bent slightly, pelvis tipped forward, eyes closed and, most importantly, feet hip-width apart, legs anchored to the wood floor.

“Every time you exhale, roots extend out of your KI and into the ground,” LuAnn encouraged. “Breathe. Feel your roots grow.”

“Now take a deep breath, and yell …”

“No!”

The collective voice was stronger now, arresting. I peeked quickly to see if anyone else looked startled, or if I was the only one still embarrassed to command our would-be attacker to “Stop!” with such gusto. I was apparently alone.

On the third try I got it. And I shouted with such enthusiasm, I felt certain no mugger/stalker/rapist would dare creep up on me in a dark alley.

We opened our eyes and shot each other congratulatory glances. But now it was time for the real lesson: figuring out how to kick the crap out of someone twice as big as you when he has his hands wrapped around your throat.

It almost made flogging seem easy.

Four weeks prior, I stood in this classroom with a considerably larger sense of trepidation. Instead of learning how to protect myself, I was being taught how to inflict pain on others—in a purely pleasurable, nonjudgmental way, of course.

read more

I’m staring at eight pit bulls. They’re all in a row and stacked on top of each other, tucked inside those plastic dog carriers that come in muted colors like light blue, beige and gray. The dogs come in a similar color scheme—some are light brown, others dark, some tan with white trim, and one a curious shade of grayish-blue. That’s the baby—only six months old and she still looks like she could herd a whole flock of sheep without the least bit of trouble. They call her Tempest.

I’m waiting for the doors to those plastic carriers to open and for those eight pit bulls to step out, one-by-one, and sit in a straight line to pose for a photo. Honestly, it’s a little intimidating. But out they come, one-by-one, and aside from the occasional escape and subsequent toe-licking from Tempest, the pits do exactly what they’re supposed to: sit for a portrait and dart playful, curious looks in my direction.

Pit bulls have gotten a bum rap. Considered in the public consciousness to be one of the most dangerous dog breeds in existence—indeed, some believe it to be the most dangerous—the pit bull is viewed as a fickle, unpredictable dog with a tendency for baby-mauling and other sorts of dastardly behavior. But the breed hasn’t always borne such a stigma.

read more

Press Releases

The Anne Frank Center

Today, only one in five U.S. states mandates that schools include the history of the Holocaust and other genocides in their curriculum. The impact of such educational scarcity has become clear: Nearly a quarter of American millennials say they’ve never heard of the Holocaust, or are unsure of whether they have. About half of all adults in the U.S., millennial or otherwise, are unable to name even one of the more than 40,000 concentration camps and ghettos from one of the darkest times in global history.

With each passing year, our collective memory becomes foggier, as new generations graduate into a culture that knows steadily less about genocide, as well as its causes and, potentially, what can be done to prevent it.

The Anne Frank Center for Mutual Respect is on a mission to reverse this trend. For the past decade, the AFC has worked with partners across the country to establish that such teaching be mandated in every state through the 50-State Holocaust & Genocide Education Initiative. In addition to the 10 states that now have such legislation, the AFC has received commitments from 17 additional states on their intention to advance this initiative, and the momentum is growing.

read more

In every culture, and in each era, the tenets of compassion, open-mindedness, and understanding are equally critical to our humanity; the need for mutual respect has no trend line. Yet throughout our global history, there have been moments in which such values have been so diluted as to seem all but invisible. One of the greatest duties we possess as citizens of this planet is to prevent the atrocities of our past from echoing into our future, and it is by fostering generosity where it is weak, and education where it is absent, that we find our greatest chance at success.

This philosophy fuels the Anne Frank Center’s mission to promote respect for all of humanity. Through a new Advisory Council established this spring—comprised of political leaders, humanitarians, social justice entrepreneurs, artists, scholars, and educators—the AFC aims to expand the reach of its ambassadors, and in so doing advance the values that are so central to that mission.

read more

Anne Frank’s name and words have become so iconic that it can be easy to forget she lived not so long ago—recently enough to still be actively remembered by the people who knew her. One of those people is Pieter Kohnstam, who knew Anne as his babysitter when he was a child in Amsterdam, before the Frank family went into hiding and his own family escaped through a series of countries, eventually settling in Argentina. While in Amsterdam, the Kohnstams were neighbors of the Franks on Merwedeplein and became close, as both families had fled Hitler’s Germany.

It is in part this experience that led Pieter and his wife, Susan, to decades of humanitarian service—promoting peace, unity, compassion, and understanding as two of the Anne Frank Center’s most inspiring volunteers. The Anne Frank Center for Mutual Respect is honoring them with the 2019 Legacy of Hope Award as part of this year’s Spirit of Anne Frank Awards (SAFA), acknowledging the Kohnstams’ tireless commitment to teaching about the Holocaust and its frightening relevance to events today.

read more

Personal Essays

Some favorites from the blog

John Steinbeck began his writing days—which is to say, most days—with a simple but strange habit. He sat at his desk and sharpened between 24 and 100 pencils.

One by one, after each was carved into its highest form, Steinbeck would lay them in the closest of two identical wooden boxes, both within arm’s distance. When the tip of one writing instrument snapped or wore dull (generally four or fives lines into its use), he dropped it into the second box and replaced it with a fresh one, immediately at hand.

He could reach without looking, eject one and select another, plucked from an orderly pile of sticks.

Each pencil laid fastidiously beside him was identical to its neighbors: the same brand (Blackwing), the same lead weight (firm, likely an F or HB), and approximately the same length (whatever the length of a brand-new pencil is, following its first sharpening).

Steinbeck used pencils while they were long and slender, when they felt to him to provide the correct balance—a shape that could propel him forward, like good running shoes; a size to help him pick and prod the right forms, like chopsticks.

read more

If you sliced open a caterpillar’s cocoon, you’d expect to find a tiny beast, a creature that would look new to you yet somehow familiar. Half caterpillar, half butterfly, perhaps a shiny and squiggly green grub just starting to sprout wings; wet, furled, squished into its soft, shrouding casing. But that’s not what you’d find.

If you plucked a cocoon from its silky strings and took a fingernail to it, you wouldn’t find an insectan chimera. You’d find no wings, no spongy body, no little nubbin legs. There would be no velveteen antennae, no eyes of iridescence. You would find goo. Just a cocoon of fibers and silk filled with sticky, yellow goo.

After a caterpillar spins itself a cocoon, it begins to break down. It doesn’t grow wings, doesn’t evolve. It devolves. It dissolves. It disintegrates. And then it rebuilds. From this unnerving and miraculous transformation comes a question: When a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, is it still the same animal? If it returns to nothing but molecules and paste before reincarnating itself, can you still call it by the same name? Or is one animal just taking the other’s place?

read more

The night was hot, with a heat that rose from gravel and dirt and the red Spanish tile in the kitchen, where for many other nights I had stood and looked out the window into the yard, awash in neighbors’ porch lights. Even porch lights look dry in New Mexico, not like those of the East, so thick you could pierce their skin and watch them bleed. Desert lights buzz like cicadas, the fluttery rumble of all those wings and photons shuffling against each other and stretching into an air so thin you wonder if it’s even there. When all else is quiet, there’s still that soft, eternal flickering. The night was hot. And quiet, for a time.

That’s the night I have come for, because that is the night that came for me.

Night is a strange, inevitable thing that has always known how to summon fear, and I’ve often answered the call. Even as a child, there was no comfort in those hours when we wait once again for daybreak, for the return of warmth and light. We are shrouded in the shadow of our own planet, half frozen. Like reptiles lacking a warm rock, we languish, slow, sleep if we’re lucky. We lay down our arms and pray no one picks them up. We pray for mercy. If I die before I wake, I pray the lord my soul to take. We’re taught to whisper the words as children, remind ourselves even then that movement and breath are temporary, that eventually we all return to stillness.

read more

There was a particular pleasure in trying to skateboard in 1995 in Boulder, Colorado, when you were 13 and shy and a girl. The real word for it was probably pride, and at that age, it was a sensation worthy of a few skinned knees.

Jessica and I had decided to do it together. We’d known each other for as long as any person can know another person outside of their direct blood lineage; we were each only in the world a matter of months before our mothers introduced us. I remember no time in my life without Jessica. She was always there, as essential to my reality as sunshine.

For a time, we lived close enough to walk, unattended, to each other’s homes, but our houses sat on opposite sides of an invisible line that divided one school district from the next. After kindergarten, we always went to different schools. It was likely a combination of these factors—a sisterly love, a social separation—that led to the continuation of our best friendship, even though Jessica was much more popular at her school than I was at mine.

I was no outcast, but managed to suspend myself in the middle-reaches of the junior high caste system, like an egg that decides to neither sink nor bob. The term “painfully shy” carries the fullest extent of its meaning in those years spanning the sixth to eighth grades. I was timid not just socially but physically, living with the persistent fear that I would somehow injure myself. I opted against learning how to ski, rollerblade, or even ride a bike. People who liked rollercoasters were insane. Gym class was an exercise in the definitions and limitations of torture. I was pretty, and I smiled a lot, and once you got to know me I was brave at least in my humor, and that’s how I survived the social turmoil of middle school.

read more

The day we found Rokan, the sky was blue, that sort of crisp, surreal cerulean that might only exist in New Mexico and other arid, sweeping landscapes that offer nearly nothing in the airways between you and the vastness of the beyond. The kind of blue that, if you stare at it for more than a few seconds, will seem to ripple and undulate, eventually throb, mimicking the rhythm in your chest. The blue will make you see atoms, electrons, the faintest flash of a quark, perhaps, wisps of the imperceptible and imperceivable. You wonder if this is what LSD feels like as it takes its hold. It blossoms. You stay until you are pulled away by your companion on the trail or the switch to a green light or your own sense of self-preservation. It is deep. The day was that kind of blue, and I’ll always remember it, because when we found him we held him to the sky.

Some of you will already know why I went in search of him; those who don’t may get the full story another day. Today, the abbreviated version is this: I felt unsafe in my home. A stranger had broken into my apartment in the middle of the night while I was sleeping. I escaped physically uninjured, but, as is the way of things, it isn’t as easy to flee psychological wounds. It was the kind of experience that, no matter how adamantly you tell yourself it won’t, will change you. I couldn’t sleep alone. I never slept in that place again.

read more

It’s quiet now at night, even in the city, roads and voices muted by the mad hush of rain. Rain against pavement is also a sound, but it slips through ears like it does through gutters, spilling over and out and rushing to sea in the way all moments and memories eventually do. But I imagine that tonight even without the rain the world would seem silent, no matter the city or bustle or subway line. Tonight is made for our quiet.

Rain in New Mexico is like destiny; every drop a karmic reward, a promise that tomorrow will come as tomorrow always has. But sometimes it doesn’t, does it? Sometimes it’s just one last night of rain or dust, and who are we to know when that night will arrive?

Out east by the sea, where the rain runs away, it’s not quite so revered. The rain comes and people stretch for umbrellas and rubber, they shake their heads after having their fill. But in the desert when the moon was full and the rain slapped against us, we ran into the yard without our shoes and spun, arms and heads to the heavens. We were younger then, and life had not yet torn us to ribbons. The rains plumped the sagebrush and lavender, and we were plumped, too, buoyed with that which had not yet washed out to sea.

read more

The first time a boy pinched my ass I was in the fifth grade. His name was Spencer. He probably did it on a dare. I slapped him across the cheek as hard as a 10-year-old girl can slap. I stomped away, red-faced, to find a corner where I could cry.

The first time I kissed a boy, it was definitely on a dare, although I liked him. I spent the night at my friend Lacey’s house. She lived in the same mobile home community as the boy, and we walked over to his place and tapped on his bedroom window. She dared us to kiss, we did, and it was sloppy and salty and strange, which is the way of first kisses. I was 13. I wondered if he liked me, too. I’m still not sure. We never kissed again, but another night he chased me around the property and I was a little scared of what would happen if he caught me. But I was faster.

The first time I told a boy I loved him, I was 17. He was mean to me, this boy. He’d started out sweet but slowly devolved. We dated on and off all throughout high school, and each time we were on he got meaner. We dated for all of senior year. I told him I loved him. He called me a dumbass. He ordered me to fetch him things, cheated openly, told me I’d look better with breast implants. Once when I was sitting down he saw a pocket of cellulite on my thigh and stared at me in disgust, asked what it was. One of the great embarrassments of my life is that I stayed for as long as I did. But that’s what happens when you’re young and insecure and beaten down by how little other people think of you. I stayed until I didn’t, until I disowned him and most of the people who came with him. Really, though, I was forced to leave.