I don’t know how old I was the first time I had an obsessive-compulsive thought. I’m not even sure of my age in the earliest memory I have of such an event, although I’ve always assumed it was 6, the number we tend to attribute to all early childhood recollections.

What I do remember is sitting in the backseat of the family minivan, my forehead rested against the window as I watched streets and scenery shift in late-afternoon sun. The back of my throat felt parched, and I imagined in that haze of golden light that I was in a desert, sand stretched like an ocean, sun baking my skin.

Perhaps that’s why the color blue came so prominently to mind, a deep sapphire round and cool to quench my thirst, appearing in a perfect circle, a tiny pool of salvation. It was one dot of blue, then another appeared, then there were six, and I found myself counting them, mentally stacking the collection into a pyramid as I tallied.

And then again I did it. Lay the base—one two three—then the next row—one two—then the top—one. And again I counted. And again.

It wasn’t so much a game as observation. There were six blue dots, and I counted them, and I stacked them, and I found myself anxious to ensure they were all evenly spaced from each other, even though they existed only in my head.

OCD is your lifelong companion, a specter you will never outgrow.

A seventh dot appeared, and I placed it at the base of my imaginary pyramid, requiring the creation of an extra for the next row, and the next, and one more that would become the new apex.

The pattern spiraled. The pyramid in my head would appear even, and then another dot would appear in the scene, and I had to place it, invent more to keep it company, keep track of a growing population.

There were six, then ten, fifteen, twenty-one, twenty-eight, thirty-six. My mind looped round and round, building pyramids, counting rows, organizing armies of blue dots. The afternoon sun cast a Saharan glow against the all the moving pictures passing by.

It was a small moment, unremarkable enough that even though it’s stuck in my memory for thirty-plus years, this is the first time I’m telling the story. To anyone.

The anecdote may not even be unique. Maybe all children experience similar mental negotiations.

The only reason I remember that afternoon in the minivan counting imagined objects, in fact, is because I couldn’t stop.

OCD evolves with you. It matures, adapts, stretches and squeezes itself into new forms. You think you’ve figured it out and it shape shifts, presenting new activities for your imagination. OCD is your lifelong companion, a specter you will never outgrow.

Of course, I knew none of that then. It would be years before I’d even be able to give that piece of myself a name.

Long before I could name it, I learned how to hide it, figured out that the way life looked to me was different than how it appeared to my friends. In a culture increasingly obsessed, if you will, with self-image, people don’t often look too far beyond themselves. It doesn’t take all that much to hide.

It would be years before I’d even be able to give that piece of myself a name.

But while you may have created a version of yourself acceptable for public consumption, an avatar that reveals only your most desirable or even tolerable traits, storms brew beneath your skin. When those tempests gather and rage, much more of you is required to keep your surface intact.

I did a good job of it, if “good” refers to the perception of others rather than the care of myself. In private, at night, under the desk, I would tap, count, retrace, circle back, begin again, and again. I would lay my hand against my chest and measure heartbeats; pick one box of cereal and then swap for it another, or maybe another, or maybe the first one again, or maybe all the way in the back; negotiate with clocks, interpreting even and odd numbers to signal answers such as yes or no, like flipping a preordained coin.

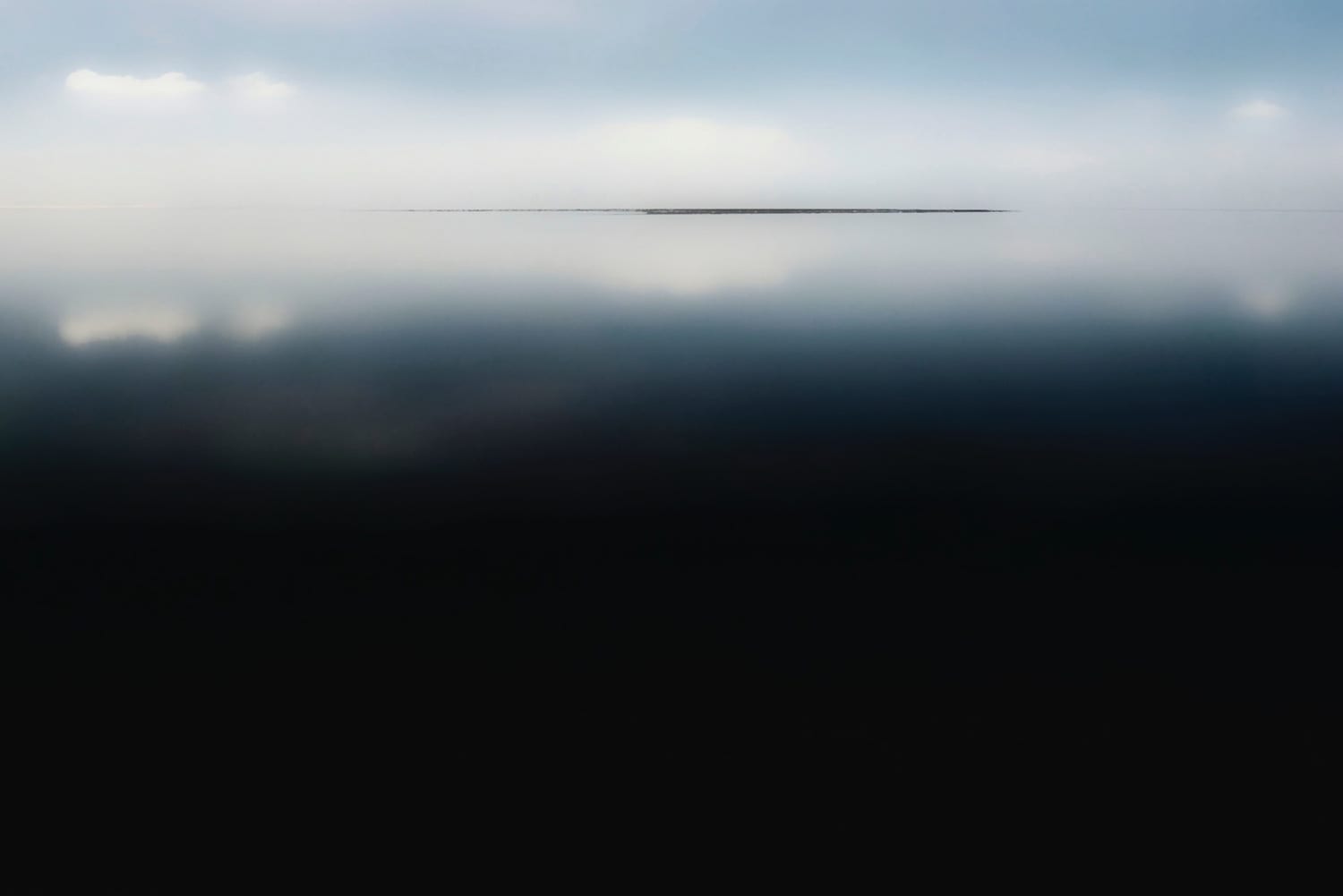

I would lie awake until sunrise, waiting for the predawn blue to glow through the curtains and light up the sky.

It still gets me that for all of those years, I feared the dark for the wrong reasons. A mysterious and sudden illness. A malfunctioning carbon-monoxide detector. Even ghosts. I was never scared of other people, and so naturally that’s exactly what came for me on the one night I almost didn’t make it to daybreak. But that’s another story.

I was on a quest for the holy grail—I wanted nothing more, yet I never really believed I would find it. I was in it for the search.

For a long time, I think I really did believe that the love in my life was conditional, that if people knew about the ticks and pulls in my brain they’d cast me out. For far too long, I worried that my romantic relationships were in ways rooted in trickery, since it was such a significant part of myself that I could not share. No one would continue to love me if they found out. No one would stay. I suppose I am still not entirely convinced it is otherwise.

Perhaps that’s why for so much of my life I chose relationships that I knew, even when I didn’t know, couldn’t last. There was only so long I could practice sleight of hand before the illusion would fall. Perhaps that’s why I idealized relationships as much as I did. I was on a quest for the holy grail—I wanted nothing more, yet I never really believed I would find it. I was in it for the search.

The shell first cracked during my senior year in college, when I went to the student health center because I worried something was wrong with my heart. My breath was rapid, my chest drumming staccato, the occasional flutter, missing a beat.

The nurse who saw me told me calmly that I was perfectly fine, and recommended that I visit the other side of the building and talk to a therapist.

People confuse a natural human desire to ascribe order to our surroundings with those three letters.

I’d heard the words obsessive-compulsive disorder before and elements of the condition felt familiar, but I was unaware of how differently it could present itself in one person versus another. Whatever my experience, I could hide it. I was no Howard Hughes. I didn’t think the words belonged to me.

When the therapist informed me, after I finally confessed those stickiest of sins, that it was clear I had OCD, my shame began ever so slowly to lift.

It wasn’t my fault. I wasn’t wrong, or dirty, or a secret that needed to be cloaked. A lot of people have OCD, which expresses itself in a multitude of directions and degrees. It looks a little different on everyone.

I began to experiment with saying the words out loud, then to other people. One friend, two. Back then I was comforted and emboldened by the fact that those initials had been so diluted by pop culture that seemingly everyone occasionally employed them. “My OCD” is still a phrase that laces the peripheries of my life, a term used to describe any quite particular preference for things being a certain way.

“Hang on, I want to get all these labels facing the same direction. It’s my OCD.”

“I’ve gotta clean the kitchen before I go to bed. It’s my OCD.”

“There’s just a hair out of place … let me fix it. It’s my OCD.”

It was many more years still until I submitted to what those three letters meant for my life.

Even today, people confuse a natural human desire to ascribe order to our surroundings with those three letters, which we all of course know stand for something much less fashionable: a diagnosed mental disorder.

These days, those misused letters stick in my teeth like caramel, their sickliness stinging right down to the nerve.

And yet, a typical hypocrite, I still find myself taking advantage of this misappropriation to gauge the reactions of new friends, ease those conversations into cool water. I’ve become quicker, though, at getting to the point. There’s less hedging.

I work at this, because the only way to help other people feel less alone, less wrong, less unfixable, less stigmatized—the only way to help myself feel less of those things, too—is to stop hiding.

It was many more years still until I submitted to what those three letters meant for my life. I never even considered taking medication, feeling that doing so would be somehow akin to giving up, worrying that one little pill would change me fundamentally—that by diminishing a less desirable part of myself, it would muffle the bits I liked as well.

Without rest, you’ll use yourself up and dream only of stillness.

When you are classified by your doctor as “high-functioning,” you take it as a compliment, a point of pride. You are clever enough, you tell yourself, to figure it out on your own.

You change your diet, exercise more, drink less alcohol and more water, prioritize sleep, establish a regularly scheduled appointment with a therapist. In other words, you do the things we should all be doing anyway. You try cognitive behavioral therapy; read blogs and books; meditate; practice self-talk, journaling. You breathe.

But most of the time, your attention is tuned toward a singular goal: staying afloat. Your head may be above water, you’re treading, you’ve got this, but eventually you’ll tire. Without rest, you’ll use yourself up and dream only of stillness.

Sometimes life is easy enough to merely float, watch for currents but otherwise let go, allow your limbs to once again firm. But on other days or weeks or months, when those storms swell large and wild, there’s no room for such luxuries. You can only negotiate with the growing demands of the fierce and roiling deep.

You survive those bouts of turmoil, but at a cost.

It was the year after someone dear to me—a shiny, heroic, utterly irreplaceable sunbeam of a person who smelled of salt and sea—shot and killed himself, two years after my mother died to cancer, three years after a relationship that had redefined me ended, that I discovered I could no longer restrain my storms. The world was a puzzle of compulsions and fear.

When those storms swell large and wild, there’s no room for such luxuries. You can only negotiate with the growing demands of the fierce and roiling deep.

I only booked an appointment with a psychiatrist at the pleading of a friend. It wasn’t the first time the idea was suggested by friends—two in particular—but on that day in 2014 when the walls were crashing in, I finally let go. I was ready to find something that could carry me.

The way I describe the beauties of Zoloft and Wellbutrin to others is this: It’s like when you have a terrible headache, and you can’t focus, and you feel sick, and all you can really do is lie there. And then you take some ibuprofen and, like magic, the headache lifts. You’re still just as much of yourself, arguably more so because that throbbing, gnawing ache is no longer obscuring the view. You can see again. The waters are clear.

Five years since the first time I woke up and told myself, reluctantly, take your medicine, I know with certainty that the kindest thing I ever did for myself was allow for the possibility of those two little pills.

She’s still in me, the OCD. She doesn’t lift like a headache. But she also doesn’t mean me any ill will, no more than a broken limb means to cause you pain. These days, she’s quieter, less prone to fits and starts. I no longer try to shoo her away, and she doesn’t dig in her heels, determined to stay.

When I see her, I say hello. And then I go about my day.

0 Comments